CARL FRIEDRICH

GAUSS

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss ( 30 April 1777 – 23 February

1855) was a German mathematician and physicist who made significant

contributions to many fields, including algebra, analysis, astronomy, differential geometry, electrostatics, etc.

Sometimes referred to as the Princeps

mathematicorum (Latin for "the foremost of

mathematicians") and "the greatest mathematician since

antiquity", Gauss had an exceptional influence in many fields of

mathematics and science, and is ranked among history's most influential

mathematicians.

Early Life

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss was born on 30

April 1777 in Brunswick (Braunschweig), in the Duchy of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (now

part of Lower Saxony, Germany), to poor, working-class

parents. His mother was illiterate and never recorded the date of his

birth, remembering only that he had been born on a Wednesday, eight days before

the Feast of the Ascension (which occurs 39

days after Easter). Gauss later solved this puzzle about his birth date in the

context of finding the date of Easter, deriving methods to compute the

date in both past and future years. He was christened and confirmed in

a church near the school he attended as a child.

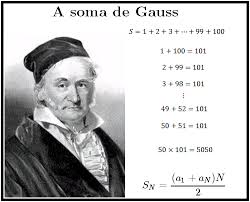

Gauss was a child

prodigy. A contested story relates that, when he was eight, he figured out

how to add up all the numbers from 1 to 100. There

are many other anecdotes about his precocity while a toddler, and he made his

first groundbreaking mathematical discoveries while still a teenager. He

completed his magnum opus, Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, in

1798, at the age of 21—though it was not published until 1801. This work was

fundamental in consolidating number theory as a discipline and has shaped the

field to the present day.

Career and

achievements

Algebra

In his 1799 doctorate in

absentia, A new proof of the theorem that every integral rational algebraic

function of one variable can be resolved into real factors of the first or

second degree, Gauss proved the fundamental theorem of algebra which

states that every non-constant single-variable polynomial with

complex coefficients has at least one complex root. Mathematicians including Jean le Rond d'Alembert had produced

false proofs before him, and Gauss's dissertation contains a critique of

d'Alembert's work. Ironically, by today's standard, Gauss's own attempt is not

acceptable, owing to the implicit use of the Jordan curve theorem. However, he subsequently

produced three other proofs, the last one in 1849 being generally rigorous. His

attempts clarified the concept of complex numbers considerably along the way.

Gauss also made important

contributions to number theory with his 1801 book Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (Latin, Arithmetical

Investigations), which, among other things, introduced the

symbol ≡ for congruence and used it in a clean

presentation of modular arithmetic, contained the first two

proofs of the law of quadratic reciprocity, developed the theories

of binary and ternary quadratic

forms, stated the class number problem for them, and showed

that a regular heptadecagon (17-sided polygon) can be constructed with straightedge

and compass. It appears that Gauss already knew the class number formula in 1801.

In addition, he proved the

following conjectured theorems:

He also

· invented the Cooley–Tukey FFT algorithm for

calculating the discrete Fourier transforms 160

years before Cooley and Tukey

Astronomy

In the same year, Italian

astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi discovered the dwarf

planet Ceres. Piazzi could only track Ceres for

somewhat more than a month, following it for three degrees across the night

sky. Then it disappeared temporarily behind the glare of the Sun. Several

months later, when Ceres should have reappeared, Piazzi could not locate it:

the mathematical tools of the time were not able to extrapolate a position from

such a scant amount of data—three degrees represent less than 1% of the total

orbit.

Gauss, who was 24 at the

time, heard about the problem and tackled it. After three months of intense

work, he predicted a position for Ceres in December 1801—just about a year

after its first sighting—and this turned out to be accurate within a

half-degree when it was rediscovered by Franz Xaver von Zach on 31 December

at Gotha, and one day later by Heinrich Olbers in Bremen.

Gauss's

method involved determining a conic

section in space, given one focus (the Sun) and the conic's

intersection with three given lines (lines of sight from the Earth, which is

itself moving on an ellipse, to the planet) and given the time it takes the

planet to traverse the arcs determined by these lines (from which the lengths

of the arcs can be calculated by Kepler's Second Law). This

problem leads to an equation of the eighth degree, of which one solution, the

Earth's orbit, is known. The solution sought is then separated from the

remaining six based on physical conditions. In this work, Gauss used

comprehensive approximation methods which he created for that purpose.

One such method was the fast Fourier transform. While this method is

traditionally attributed to a 1965 paper by J. W.

Cooley and J. W. Tukey,[54] Gauss

developed it as a trigonometric interpolation method. His paper, Theoria

Interpolationis Methodo Nova Tractata, was only published posthumously in

Volume 3 of his collected works. This paper predates the first presentation

by Joseph Fourier on the subject in 1807.

Zach noted that "without

the intelligent work and calculations of Doctor Gauss we might not have found

Ceres again". Though Gauss had up to that point been financially supported

by his stipend from the Duke, he doubted the security of this arrangement, and

also did not believe pure mathematics to be important enough to deserve

support. Thus he sought a position in astronomy, and in 1807 was appointed

Professor of Astronomy and Director of the astronomical observatory in Göttingen, a post he held for

the remainder of his life.

The discovery of Ceres led

Gauss to his work on a theory of the motion of planetoids disturbed by large

planets, eventually published in 1809 as Theoria motus corporum

coelestium in sectionibus conicis solem ambientum (Theory of motion of

the celestial bodies moving in conic sections around the Sun). In the process,

he so streamlined the cumbersome mathematics of 18th-century orbital prediction

that his work remains a cornerstone of astronomical computation. It introduced

the Gaussian gravitational constant,

and contained an influential treatment of the method

of least squares, a procedure used in all sciences to this day to minimize

the impact of measurement error.

Gauss proved the method under

the assumption of normally distributed errors (see Gauss–Markov theorem; see also Gaussian). The

method had been described earlier by Adrien-Marie Legendre in 1805, but Gauss

claimed that he had been using it since 1794 or 1795. In the history of

statistics, this disagreement is called the "priority dispute over the discovery

of the method of least squares."

Geodetic

survey

In 1818 Gauss, putting his

calculation skills to practical use, carried out a geodetic survey of

the Kingdom of Hanover, linking up with previous

Danish surveys. To aid the survey, Gauss invented the heliotrope, an instrument that uses a

mirror to reflect sunlight over great distances, to measure positions.

Non-Euclidean

geometries

Gauss also claimed to have

discovered the possibility of non-Euclidean geometries but never

published it. This discovery was a major paradigm shift in mathematics, as it

freed mathematicians from the mistaken belief that Euclid's axioms were the

only way to make geometry consistent and non-contradictory.

Research on these geometries

led to, among other things, Einstein's

theory of general relativity, which describes the universe as non-Euclidean.

His friend Farkas Wolfgang Bolyai with whom Gauss had sworn

"brotherhood and the banner of truth" as a student, had tried in vain

for many years to prove the parallel postulate from Euclid's other axioms of

geometry.

Bolyai's son, János

Bolyai, discovered non-Euclidean geometry in 1829; his work was published

in 1832. After seeing it, Gauss wrote to Farkas Bolyai: "To praise it

would amount to praising myself. For the entire content of the work ...

coincides almost exactly with my own meditations which have occupied my mind

for the past thirty or thirty-five years."

This unproved statement put a

strain on his relationship with Bolyai who thought that Gauss was

"stealing" his idea.

Letters from Gauss years

before 1829 reveal him obscurely discussing the problem of parallel

lines. Waldo Dunnington, a biographer of Gauss, argues

in Gauss, Titan of Sciencethat Gauss was in fact in full possession

of non-Euclidean geometry long before it was published by Bolyai, but that he

refused to publish any of it because of his fear of controversy.

Theorema

Egregium

The geodetic survey of

Hanover, which required Gauss to spend summers traveling on horseback for a

decade, fueled Gauss's interest in differential geometry and topology,

fields of mathematics dealing with curves and surfaces. Among other things, he came up with

the notion of Gaussian curvature. This led in 1828 to an

important theorem, the Theorema

Egregium (remarkable theorem), establishing an important

property of the notion of curvature. Informally, the theorem says that the curvature

of a surface can be determined entirely by measuring angles and distances on

the surface.

That is, curvature does not

depend on how the surface might be embedded in

3-dimensional space or 2-dimensional space.

In 1821, he was made a

foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Gauss was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and

Sciences in 1822.

Magnetism

In 1831, Gauss developed a

fruitful collaboration with the physics professor Wilhelm Weber, leading to new knowledge

in magnetism (including

finding a representation for the unit of magnetism in terms of mass, charge,

and time) and the discovery of Kirchhoff's circuit laws in

electricity. It was during this time that he formulated his namesake law.

They constructed the first electromechanical telegraph in

1833, which connected the observatory with the institute for physics in

Göttingen. Gauss ordered a magnetic observatory to

be built in the garden of the observatory, and with Weber founded the

"Magnetischer Verein" (magnetic club in German), which

supported measurements of Earth's magnetic field in many regions of the world.

He developed a method of measuring the horizontal intensity of the magnetic

field which was in use well into the second half of the 20th century, and

worked out the mathematical theory for separating the inner and outer (magnetospheric)

sources of Earth's magnetic field.

Later years

and death

Gauss remained mentally

active into his old age, even while suffering from gout and general

unhappiness. For example, at the age of 62, he taught himself

Russian.

In 1840, Gauss published his

influential Dioptrische Untersuchungen, in which he gave the first

systematic analysis on the formation of images under a paraxial approximation (Gaussian

optics). Among his results, Gauss showed that under a paraxial

approximation an optical system can be characterized by its cardinal points and he

derived the Gaussian lens formula.

In 1845, he became an

associated member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands; when that became

the Royal Netherlands

Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1851, he joined as a foreign member.

In 1854, Gauss selected the

topic for Bernhard Riemann's Habilitationsvortrag,

"Über die Hypothesen, welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen"

(habilitation lecture About the hypotheses that underlie Geometry). On

the way home from Riemann's lecture, Weber reported that Gauss was full of

praise and excitement.

On 23 February 1855, Gauss

died of a heart attack in Göttingen (then Kingdom of Hanover and now Lower Saxony);

he is interred in the Albani

Cemetery there. Two people gave eulogies at his funeral: Gauss's

son-in-law Heinrich Ewald, and Wolfgang Sartorius von

Waltershausen, who was Gauss's close friend and biographer. Gauss's brain

was preserved and was studied by Rudolf

Wagner, who found its mass to be slightly above average, at

1,492 grams, and the cerebral area equal to 219,588 square millimetres

(340.362 square inches). Highly developed convolutions were also found, which

in the early 20th century were suggested as the explanation of his genius.

ReplyDeleteToday I was surfing on the internet & found this article I read it & it is really amazing articles on the internet on this topic thanks for sharing such an amazing article

Social Work Assignments